Adventures in Japan: 12 and 13 January 2018 – Fukushima now – 7 years later

Written by Michelle Krüger

The following article, originally published in the website wêreldwyd, was written by my sister, Michelle, who taught English in Fukushima in the years following the earthquake. She wrote the piece almost 7 years ago. She paid me a visit this December and said that I am welcome to share it with my audience.

An Afrikaans version is also available here.

“Following a major earthquake, a 15-metre tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of three Fukushima Daiichi reactors, causing a nuclear accident on 11 March 2011.”

Six months ago, I came to Japan and was placed in the Fukushima Prefecture. The most common reaction from family and friends was: “Is it safe to live there?” and “Isn’t it uninhabitable?” or “What about the radiation?”.

The ignorance of people sometimes astounds me, as many of these comments were made by people who are well-educated individuals, yet sadly ignorant about the March 2011 event. Many of my family and friends were possibly not aware that I chose Fukushima as an option when I had to indicate where I would like to live, as I wanted to see and experience what these people had gone through.

On 12 and 13 January 2018, I was fortunate enough to be able to experience some parts of it, as 23 other ALTs and I were given the opportunity to see the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (NPS), The Naraha Remote Technology Development Centre (Naraha Centre) and some parts of the exclusion zone. We were granted the opportunity to speak to professionals in the field, who explained to us what happened on that dreadful day.

We spoke to locals and spent time in Namie to better grasp the reality of what a lot of people still face due to the disaster, and how it has left them displaced in society. The people of Fukushima are still facing a lot of scrutiny in and outside of Japan and I am fortunate enough that – after that weekend – I could say I now know better.

The study tour aimed to show foreigners and foreign residents not only the damage sustained by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster of that day in 2011, but also the current recovery efforts that are being made, even though they do not come into contact with mainstream media.

One of the very reasons for coming to Japan and to Fukushima itself, was for being able to one day visit the exclusion zone and educate me on the disaster of 11 March 2011. I now realise how fortunate I am to have been granted this opportunity. It was a privilege to be allowed to enter the premises of the Fukushima Daiichi NPS itself as well as the difficult-to-return-zone of Okuma, along with the former evacuation areas of Naraha, Tomioka, Namie and Odaka.

While the Fukushima Prefecture may have a bad reputation due to the nuclear disaster – both inside and outside of Japan – it is important to know that what you might have heard may not be true.

This year marks the seventh anniversary of the triple disaster.

Day one

The ALTs departed from various locations within the Prefecture to meet for a briefing in Tomioka before our departure to the Fukushima Daiichi NPS.

At the briefing we were told exactly what happened within the reactors to cause them to explode. We were also informed of the current clean-up processes in place, what had already been done and the plans which are being followed to rebuild and clean the reactors. This is not a process which will be completed within the next month or so but will rather be a long-term project.

Karin Taira, one of the organisers of the study tour, also had a Geiger counter (a device for measuring radioactivity by detecting and counting ionising particles) which she was to give to the group for two days. Cormac, our local scientist, gladly jumped at the opportunity and volunteered to keep it on him. (In all honesty, no one else would have had any idea how to read it, let alone what to do with it!) Cormac was ecstatic to be able to have his toy for the next two days and constantly updated us all on the radioactivity within the areas. I am fairly sure not many people were even aware what the numbers meant, as they agreed in confirmation or shook their heads. It was comforting to know we had someone with an immense passion and love for science with us, who would certainly inform us if we were unsafe.

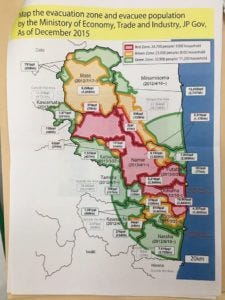

The image above depicts the evacuation zone as of 2015. The zone has decreased in size since then, but the red area remains the same even now. The red areas are considered difficult-to-return-to zones and it will take a considerable time before these areas are habitable again.

Our next stop was the Fukushima Daiichi NPS.

We were requested to leave all phones and metal items behind at the briefing facility. We were not allowed to take any photos of our own – for privacy reasons – but we were later provided with pictures taken by the tour organisers.

The image below shows the sea area status around the power plant. Scientists are actively monitoring the radioactivity around the plant – even so seven years on.

Once we arrived at the power plant, we were taken inside and given access cards. We went through security and were taken to another briefing room where we were instructed to wear the vests given to us. Each of us was also given a personal Geiger counter to keep on us to ensure that we were not exposed to dangerous levels of radiation.

We then all got onto the tour bus to explore and learn about the facility. We were taken right to the heart of the accident, to reactors 1, 2, 3. Only Reactor 2 did not explode, as the blow-out panel allowed the hydrogen gas to escape; reactors 1 and 3, however, melted down. Due to maintenance on reactors 4, 5 and 6 on that particular day, they were offline and not affected by the tsunami. We could see the damage caused by the explosion – it was devastating to see even now, seven years after. The cleaning process has been a slow and careful one, as people cannot enter the area for prolonged periods of time. Prolonged periods of exposure to radiation can be detrimental to one’s health and possibly even fatal. Within the power plant there are workers tirelessly working to decommission the plant. Many parts of the plant have not yet been cleaned of debris. The plant also makes use of some robots to help clean the area.

We were also shown the waterlines of where the tsunami had hit (17 m high) afterwards.

Within the facility we were also shown storage compartments of where the reactors’ fuel rods were kept. The fuel rods need to completely cool down before the boxes in which they are kept are sealed. Since these rods are still radioactive, they cannot be exposed to open air.

The image above shows four of the six compression chambers. All 1 535 of the fuel rods were successfully retrieved and removed from the compression chambers.

We were also shown the new cooling system that is now in place for the reactors and what measures are being taken to ensure that another disaster does not occur. The new cooling system consists of cold brine that is pumped at around -30 °C. The salt content prevents the brine from freezing, but the brine then freezes the water in the surrounding soil and this creates a frozen soil barrier that normal groundwater cannot penetrate.

On the premises we also saw many white boxes among the debris. These initially looked like office cabinets, but we soon found out that they were there for the sole purpose of being burnt later. Inside of these cabinet-like storage units were gloves, protective work gear and boots from the workers. These clothing items must be burnt as they were exposed to radiation for prolonged periods and cannot be worn again.

Other strange things we saw in the facility was over 800 cars. These cars are mostly not in use as they have been exposed to radiation, directly because of the explosion and contamination of water. Most of these cars will possibly never run again. Although some vehicles are used within the facility, they are not allowed outside. The amount of time needed for these vehicles to not be radioactive again would amount to about 500 years. Sure, the cars could be broken into smaller pieces before being burnt, but that is not an option at this time. The power plant personnel also do not exactly know what to do with the cars, as they cannot be used for transportation. For now, they are only stored on the premises.

The next stop for the day was the Naraha Centre. The remote technologies required for decommissioning the plant are developed and tested at this facility. Our group was offered a chance to see what they had been working on since the disaster back in 2011.

The next photo is of a description of the Naraha Centre and what they do. This outlines some of the major projects currently in development to aid with the eventual decommissioning of the plant.

In the facility they have a mock-up test area that is meant to be a replica of one of the components of the initial reactor. Since a sizable portion of the debris within the reactors is still under water, an underwater robot has been developed and is currently being tested on its ability to gather information from within the reactor.

Another robot that is currently being tested is one with the ability to climb stairs. There are also virtual reality systems in place to get a virtual look inside the reactor for the planning of eventual exploration inside the reactors. The people at the facility were excited to show us what they’ve been working on and are hopeful for the future, which – amid everything else we saw – was a welcomed change.

Not pictured is the underwater testing chamber and robots that were on-site. Researchers were able to create a robot that can work underwater. Surprisingly, while the underwater robot is quite heavy, it has lower gravity than the water it works in, so if its cable is cut or it stops functioning, the robot will rise to the surface for easy retrieval.

The robot testing pool is a large tank made of metal that is 4,5 m in diameter and 5 m deep. The robot has to be able to work in water of varying temperatures, as well as salt water due to seawater having seeped into the Primary Containment Vessels (PCVs) during the tsunami in 2011. The final robot that we saw before leaving the facility was a drone.

The drones are used to survey the reactors and to assess the damage caused by the explosion. It can give the technicians a good bird’s-eye view of the area, take pictures and better assess the plan or course of action.

The next stop for the day was the Tenjin Cape Sports Park in Naraha. The park offers a clear view of the coastline. It also has information placards showing just how far the tsunami had made its way inland in 2011. At Tenjin Cape Sports Park you can also see the second Fukushima NPS and seawalls which were built to protect the coastline.

The Futabaya Ryokan is owned by a woman named Tomoko Kobayashi, who was one of the first residents of the Odaka area of Minamisoma City to return daily. This was in 2013 after the government allowed former residents to visit during the day.

Tomoko Kobayashi is an amazing woman whose strength, hope and constant smile made a deep impression on all of us. Tomoko has worked persistently and consistently over the past five years to bring life back to the Odaka area. She has unintentionally become the face of revitalisation for the Odaka region because of this. Tomoko was even able to visit Chernobyl, Ukraine, a total of three times since the 2011 disaster to share and learn from the nuclear disaster there.

Tomoko is also an innovative entrepreneur. Wracking her brain for ideas as to how to bring to fruition her simple wish of “a town full of life”, she first started planting flowers outside of Odaka Station, still abandoned at the time, days after residents were able to visit during the day. From there she has gone on to run the ryokan that her parents owned so that people would have a place to stay should they return to the area. She serves delicious food made with locally grown ingredients to showcase that the local produce is safe to eat. She even prepared the evening’s dinner and the next day’s breakfast for all 24 of us staying at the inn. She has also started a brand of salad dressings using rapeseed oil from the flowers grown in the area to further support its recovery. (Read more here: https://uk.lush.com/article/soapbox-minamisoma-rapeseed-project)

Once Tomoko finished sharing her testimony, the room fell completely silent, and remained so. Tomoko simply laughed and said that we should smile and laugh too, because it was already too silent in the town. She wanted to fill the walls of the ryokan with the sounds of people enjoying themselves. I asked Tomoko what her vision is for the next eight years and what she would like to see when she sits, retired, on her porch. Tomoko answered: “I would like to see people walking around the town, hear children’s voices, and see elderly folk like myself living out their lives to the fullest.”