A few months ago, I wrote a document with a few colleagues where we criticized the data on nuclear power that were used by the South African Presidential Climate Commission - a body that had a known ‘anti nuclear activist” on its panel - a clear conflict of interest. After considerable effort by many within the nuclear industry, the narrative has finally shifted, and the country is returning to its historical path of developing nuclear power along the coastal cities with the eventual end goal of replacing the entire coal fleet within the interior with nuclear power.

The government has yielded to popular pressure from numerous engineers and union members, signaling the potential realization of a new 2000 MW pressure water reactor and an additional 500 MW allocated to small modular reactors. Although the project is not set to commence immediately due to lingering details requiring clarification, it is worthwhile to pause and reflect after a year of ongoing debate. It seems that the voices of numerous engineers within the energy sector are finally gaining recognition and that the renewable “harvard boys” are a bit in retreat.

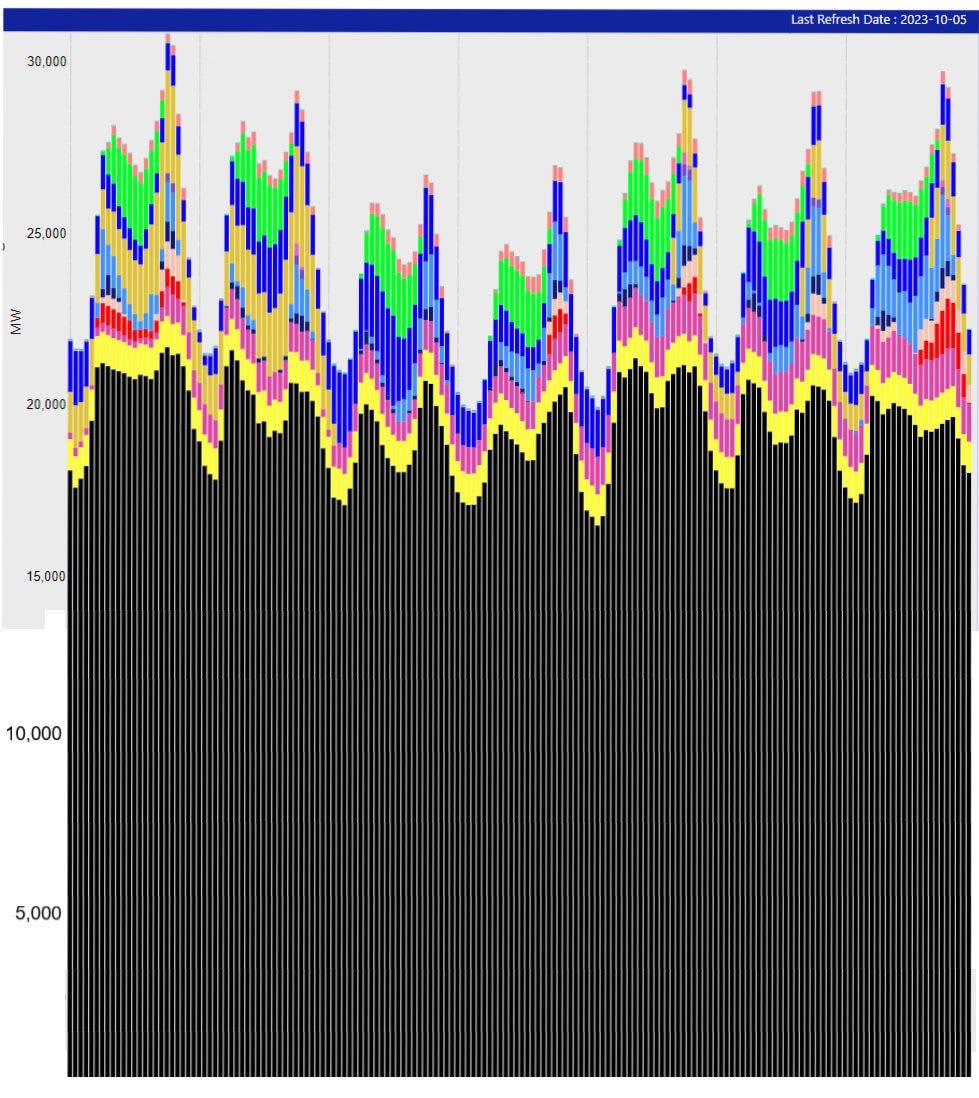

The case for nuclear power in South Africa was well understood by the Apartheid System Planners as it was incorporated into the energy component of the total strategy - the policy that a nation falls back on when it’s survival becomes under threat. As the 25th driest country globally, and in the absence of waterpower, South Africa essentially has two choices to maintain sufficient baseload capacity, coal and nuclear power. The intermittency problem of renewables will be difficult to handle without the widespread availability of water, and therefore we cannot that easily move towards “flexible” options and a pricing mechanism that trades in kilowatt-hours. As I argued in parliament, the move will destroy the coal fleet and leave us all poorer.

The recognition of the necessity for nuclear energy is so widely embraced by the broader public that opinion polls indicate it as one of the few issues on which the Afrikaners and the black communities, two historical rivals, almost unanimously agree on.

For South Africa to persist as an integral nation, it is crucial to envision a long-term coal-to-nuclear transition. This is particularly important to guarantee that communities in the Mpumalanga coal regions do not face significant disruptions to their lives during the energy transition. It is entirely possible to prevent them to be subjected to population stress and displacement by rebuilding nuclear power stations on the exact location of the coal fleet.

While coal will continue to be the backbone of the South African industrial economy for decades to come, there is now a recognition within the corridors of power that harnessing the power of the atom offers a viable path for South Africa to maintain industrial competitiveness through investment in baseload capacity.

Is this the start of South Africa's equivalent of the Messmer Plan that envisions the substitution of "dirty" King Coal with Nuclear Power?