There is a long history of activists exaggerating minor risks, with notable examples including the panic over food poisoning, unknown diseases, ozone layer depletion, excessive speeding, acid rain, fear of immigrants, and the alleged harms of secondhand smoke.

While activists are not necessarily wrong to raise public awareness on the issues, they often do so by inflating the risks disproportionately and when the issue reaches critical mass, groupthink can set in. Several books have been written about this phenomenon, such as Christopher Booker’s Scared to Death: From BSE to Global Warming and Charles Mackay’s classic Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

Once a “scientific” or pseudoscientific belief takes hold among the political elite, governments tend to overreact in their attempts “to address it”. Think of the responses to COVID-19, the panic over HIV/AIDS, the “War on Terrorism,” and never ending solutions for “decarbonising the economy”. These have led to significant resources being wasted on ineffective solutions such as hydrogen, carbon capture, government promotion of male circumcision, and the pointless lockdowns, and fruitless wars in the Middle East (twice against Iraq that most Americans couldn’t point to on the map).

A new contender for the panic du jour is texting and driving. As is typical, activists are not wrong for pointing out the obvious: phone distractions take eyes off the road. However, one would expect drivers to have the common sense not to text during rush hour, just as they would avoid reading a newspaper or tuning the radio during such times. Is there really significant harm in texting at a red light or on a quiet road at night?

Likely not, because there are a few obvious facts about highway engineering (which is a sub-set of civil engineering) that casts doubt on the claim that “texting increases your risk by 23 times!”

Traffic density, not speed, is the biggest predictor of accidents. Adjusting travel times to avoid peak hours reduces risk.

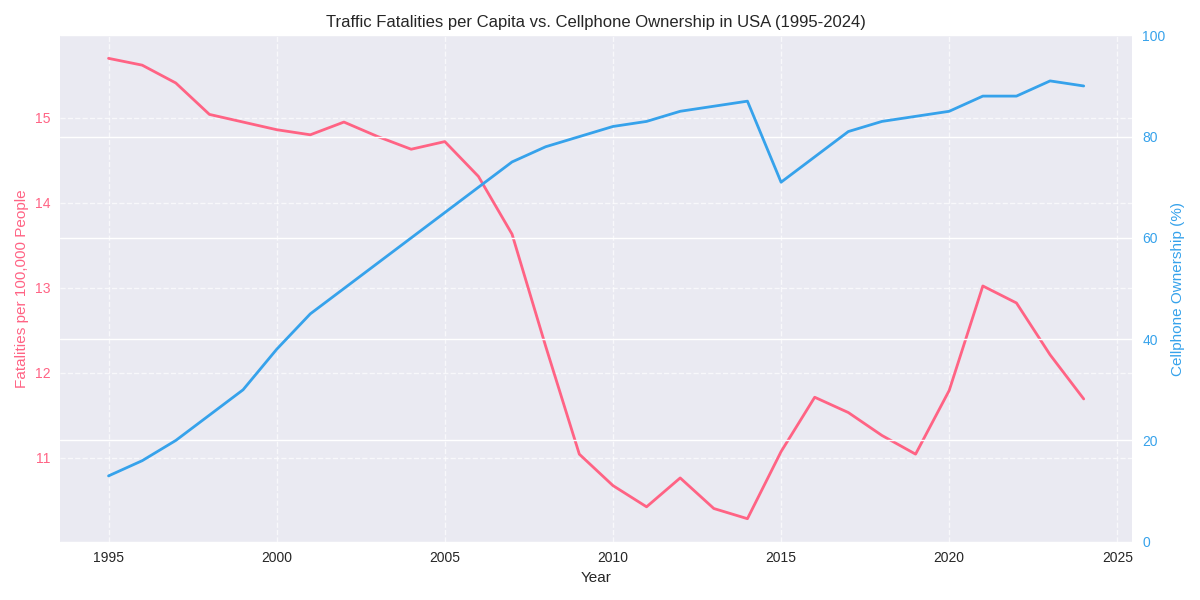

Traffic fatalities have declined since seatbelts were introduced in the 1980s, despite rising cellphone use. If correlation implied causation, one might mistakenly infer that cellphones reduce accidents?

In 2024, the U.S. recorded approximately 40,990 traffic deaths, with about 410 attributed to texting and driving in 2021, roughly 1% of the total.

The claim that texting is “23 times riskier” comes from a flawed study on truck drivers, lacking confidence intervals or margin of error.

Meta-analyses suggest texting increases near-accident risk by 3 to 4 times. Epidemiologists often dismiss relative risks below 2 due to confounding factors.

Crashes involving phones often involve individuals already prone to risky behavior, like teenage drivers.

Banning texting and driving won’t eliminate it. Rather, technological solutions like voice-to-text systems could enable safer communication.

It is also plausible that with fewer drivers due to services like Uber, police departments may enforce texting bans to maintain revenue.

Although texting and driving poses a small, yet measurable risk, its dangers have been overstated, and much like past societal panics there is a new panic over tiny effects.

Under ideal conditions public policy should be based on measurable risks, yet the past experience shows that it’s based on political considerations once the groupthink sets in.

Texting and driving is the latest issue in the list of unending series of fears.

Texting and driving is a display of arrogance and ignorance as well as disrespect of other public road users. That is it simply put

Good article and good references for historical context. Thanks!