Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine may be paid for with its oil and gas sales to Europe, but this gift is one that may stop giving. Russia’s oil resources are increasingly located in the hardest to reach areas, and far from the markets, notably in East Asia, which could conceivably replace the EU.

The mistake that many analysts make about Russian Gas is that they don’t distinguish between the pre- and post soviet gasfields. The two largest Russian gasfields, Urengoy and Yamburg were built in the 1970s during the Leonid Brezhnev years. As was the case under communist rule, the politburo had central control over the nation’s gas infrastructure and decisions were made when economic common sense as well as human rights were not taken into consideration. The debt for these large projects were enormous, but they were absorbed by the sweat and blood of those who lived under the red flag.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the newly founded Russian state under Boris Yeltsin enacted a series of privatization reforms, as the country moved from a command economy to a market economy. Under advice of the Harvard Boys public utility companies like Gazprom handed out shares to the public in exchange for vouchers.

“Gazprom began to distribute shares under the voucher method. (Each Russian citizen received vouchers to purchase shares of formerly state-owned companies). By 1994, 33% of Gazprom's shares had been bought by 747,000 members of the public, mostly in exchange for vouchers. Fifteen percent of the stock was allocated to Gazprom employees.”

In theory structural reform were supposed to bring market capitalism and all its blessings to Russia, but in practice they laid the seeds for a feudal oligarchy which quickly moved to exploit the system and strip mine the national assets while simultaneously plundering the treasury. By 1998 it became clear that the reforms were a failure.

“After seven years of economic “reform” financed by billions of dollars in U.S. and other Western aid, subsidized loans and rescheduled debt, the majority of Russian people find themselves worse off economically. The privatization drive that was supposed to reap the fruits of the free market instead helped to create a system of tycoon capitalism run for the benefit of a corrupt political oligarchy that has appropriated hundreds of millions of dollars of Western aid and plundered Russia’s wealth.”

The political consequences were devastating as ordinary Russians experienced life expectancy falling by almost 10 years during peace time and hyperinflation setting in. The late Russian expert, Dr. Stephen Cohen described the horrific conditions in Russia in 1998 as he pleaded to the US public to “help Russia”.

“Most Russians lack money even for essential goods and services. (Wage arrears to federal employees alone, including soldiers and schoolteachers, exceed $4 billion and are growing.) That is one important reason the Primakov government has to print new rubles despite strong US disapproval. The IMF should release the remaining $13 billion in new loans promised in July to the previous Russian government but withheld from Primakov’s, the first installment of $4.3 billion specifically to back rubles for long-overdue wages and pensions. This would directly help Russians in distress and avert hyperinflation.”

Putin came to power on the backdrop of the economic devastation and failings/humiliations of the Yeltsin years. He moved quickly to use the state majority shareholder’s positions to make his own political appointees in Gazprom - who still held a monopoly license over Russian Gas. In the year 2000 he fired Gazprom’s founder and then CEO Rem Vyakhirev, replacing him with his own political appointees like Dmitri Medvedev and Alexi Milner. Their task was to end asset stripping so that Gazprom could be run like a proper utility and put an end to Vyakhirev’s private family fiefdom.

But another unintended consequence of privatization was that Gazprom inherited the natural gas infrastructure from the USSR without having to pay much debt on them and this situation gave the Russians a competitive advantage when selling to EU markets. All that Gazprom had to do was to pay the operations and transport cost. Realizing that eventually they won’t have the Soviet built gasfields forever Gazprom started looking at laying a new 4,107 kilometres (2,552 mile) Pipeline to the untapped Yamal region that was eventually fully commissioned in 2006. The Yamal-Europe pipeline connects Russia’s Yamal Peninsula and Western Siberia with Poland and Germany, through Belarus. For reference, the length of the pipeline is more than twice the distance between Berlin and Moscow.

Already in 2007 the German Newspaper Der Spiegel started asking critical questions about this pipeline and Russia’s ability to supply gas to Europe forever. The Yamal region is located in the far north in increasingly harsh environmental conditions.

But the gas exploration teams are operating in highly challenging terrain. "Yamal is probably the world's most difficult extraction region," says Roland Götz, an expert on Russia at the Berlin-based German Institute for International and Security Affairs. The peninsula is covered with countless rivers and lakes, completely impassible in the summer, and its coastlines are surrounded by shifting masses of pack ice that sometimes tear meter-deep gashes into the ocean floor, making it difficult, if not impossible, to lay pipelines.”

The sentiment was shared 10 years later in 2017 by Dr. Frank Umbach Research Director at the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security. The Yamal gas was simply too expensive and could not compete with low gas prices.

Yamal also involves Russia’s most advanced LNG project. Its shareholders include PAO Novatek (with a 50.1 percent stake), France’s Total S.A. (20 percent), China’s CNPC (20 percent) and China’s Silk Road Fund (9.9 percent). The huge $27 billion project (involving three liquefaction trains, each with a total capacity of 5.5 million tons) starts operation at the end of this year when the first train opens (the full capacity of 16.5 mt is to be reached by 2022/23). However, the venture’s business plan was built on the expectation of global oil prices above $60 per barrel; it is unlikely to be profitable with crude hovering near $45gas fields.

Then in 2019 the Haque Centre for Strategic studies came out with an even more critical report that questioned Russia’s unsustainable business model.

In contrast to Russia’s more limited oil reserves its natural gas reserves are the largest in the world. The challenge here is not to produce the gas but to transport it and sell it at a profit. The rise of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) shipping now enables the monetization of remote gas reserves (and these are plentiful) throughout the world. US shale gas is increasingly providing a soft ceiling for gas prices, as US shale oil has done for oil prices since 2014. Russia will remain the key supplier of gas for the European Union (EU) but with the advance of LNG, abundant LNG import capacity within the EU and the liberalization of European gas markets, its influence on gas prices has diminished.

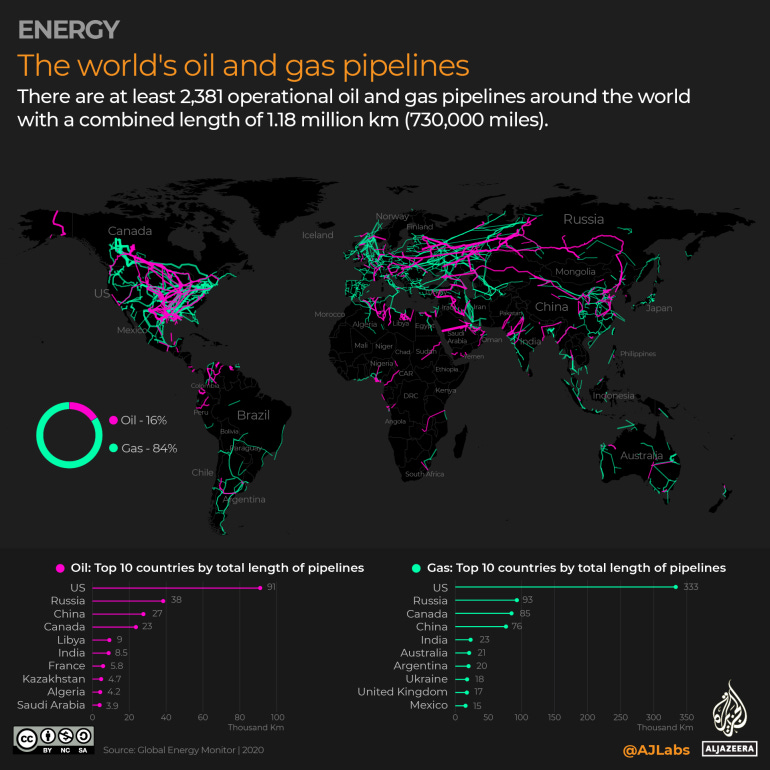

Clearly Russia was failing to monetize its reserves while America was winning the LNG Goldrush. The obstacle has always been Geography and a map of the world’s gas pipelines shows this clearly. With the sanctions underway, the Russians have put themselves into yet another quagmire. What do they do with the gas that is currently flowing if the EU decides to push through with the sanctions?

There currently isn’t pipeline that connects the eastern to western Siberian gasfields. Therefore Russia cannot just sell its gas on the east Asian markets and if they stop pumping they risk damage to their own upstream infrastructure if the pressure rises.

Source: AJ Labs

The recent high ruble or gold rush might sound impressive for as long as the Europeans are willing to buy Russian gas, but what are those who claim that Putin’s move was “genius” are going to say when Russian gas is simply too expensive in comparison with other sources like American LNG?

If the history of this war taught us anything, it’s the lesson that William Cassey, Ronald Reagan’s CIA Director taught the Soviet Union, the price of extraction and not the quantity of resources in the ground is what matters.

Last week I dug into this question in conversation with Rudolph Hubert, a LNG expert based in Austria.