Yes, you can run a coal plant far beyond its lifetime.

There is no relationship between age and performance

South Africans have been sold the false meme that a coal power station has to be retired at the end of its design life. As an civil engineer who has designed nuclear, LNG and offshore wind structures, I find the ignorance of what a design life is to be astonishing.

Structural engineers add a safety factor to our design to predict behaviour into the future. The 40 year design life number is based on a planned obsolescence assumption that generally takes into account fatigue, and other forms of infrastructure decay as the limiting factors.

But the truth is that a design life doesn’t mean that a plant will stop working at that life, the cost to keep it running might just go up with degradation. The degradation factor is a function of operations and maintenance.

Eskom’s data shows that quite well, there is simply no relationship between performance and the age of a plant. In fact it’s the newest plants that have the most problems

Eskom’s latest EAF data, shared by electricity minister Dr Kgosientso Ramokgopa, shows that age is not a big factor in breakdowns and poor performance.

Three of the newest power stations — Kusile (37%), Majuba (48%), and Kendal (47%) — have some of the worst EAF of all plants in Eskom’s fleet.

Eskom’s oldest power stations — Camden (70%) and Grootvlei (90%) — have some of the best EAF of all plants in Eskom’s fleet.

The EAF data further showed that Tutuka (26%), rife with corruption and mismanagement, has a much worse EAF than other power stations of the same age, like Lethabo (74%) and Matimba (75%).

As can be seen in the graph below, the Americans are almost achieving up to 90 years with their coal power stations, and as it turns out the smaller power stations actually run longer than the larger ones.

South Africa has many 300 MW coal power stations that can easily achieve that, in fact they were build for that reason!

Coal plants usually aren’t built with a specific planned or enforced retirement age. Retirements largely occur either when the cost of operating a plant exceeds expected revenue or when operating costs exceed the plant’s value to the power system, such as its value in providing reliability to the electric grid

As Koeberg’s team has shown us, within 1 year (with relative delays included) a power station can be overhauled to last for another 20 years. If it can be done with Nuclear Power, a far more complex technology, then there is no reason why it cannot be done with coal in a shorter period of time.

As I argued last week, South Africa underestimates the value of maintenance, whether it’s transnet, water or electricity, and we are always trying to walk from something old to something new.

Unfortunately with electricity infrastructure, you simply cannot run away from it, because it will exaggerate the rolling blackouts and the broken coal will stare you, again, in the face.

Eskom’s focus should be to fix the broken coal fleet. It remains the fastest way to alleviate the worst of load shedding and it’s only then that the other ambitious ideas should take priority.

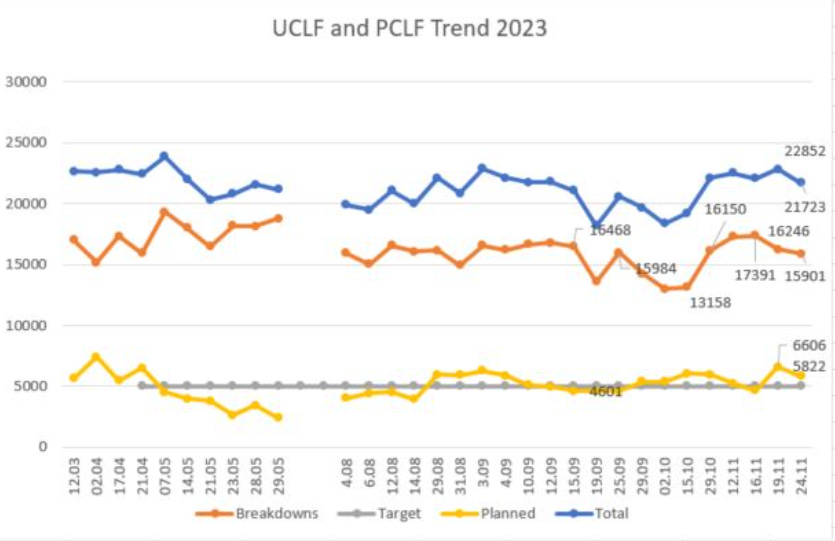

If half of the Unplanned Capacity Loss Factor (UCLF) comes online, then South Africa doesn’t just end loadshedding, but also has excess Capacity to allow for economic growth.

There is no need for more power stations (with the possible exception of LNG for emergency power), until we achieved energy security.

Simply fix what is broken.

Fully functional after 90 years. That is impressive.

This should have hit me like a ton of bricks long before now. It's hitting me like a tons of bricks now though, so at least it's happening.

Civil (water) engineer here. I have long wondered why "life cycles" are assigned to structures like power plants and other capital assets. Why do we not design for "perpetuity" as our forebears such as the Romans did. Furthermore, why do our materials not seem to last like theirs did - our concrete mixes, for example, do not seem capable of lasting two millenia.

Your article (I think) unlocked it for me. As with all things in the US, we have constructed a system where total replacement at the end of the service life will always be more cost effective than ongoing O&M. Do we design for degradation? I don't know, but we would seem to allow, at least, for book value to reach such a degraded value at the end of the service life and to be so low that when we anticipate a new analysis to be done that compares ongoing annualized maintenance costs added to a constantly depreciating asset it never makes sense not to just "re-invest" in a new facility. We are designing and building to literally match a straight-line depreciation curve and knowing that we intend to just dump capital assets at time t in the future. I guess what I'm saying is that it hits me that it's all deliberate, as least here in the States. Capital budgeting and planning is a premeditated act of short to mid-term planning and completely ignores any alternative that might plan for effective O&M to keep a facility such as an power plant or wastewater plant operational long after we're dead.

As engineers, could we be accused of borderline abuses of ethics in allowing and facilitating such wasteful practices?