There never was a Russian South African Nuclear Deal

Contributing authors: Leon Louw and Olivia Vaughan

The claims of a Nuclear Deal between the South African Government and the Jacob Zuma administration stem from what can be called, at best, sloppy journalism, and an astonishing lack of knowledge on how nuclear procurement and commercial contracting works.

In 2016, I was granted a scholarship to do a MSc in Civil Nuclear Engineering in France at the École Spéciale des Travaux Publics (ESTP Paris). It turned out to be a coincidence that I enrolled for my master’s degree at a time when the South African Government and Eskom was deliberating on procuring 9,6 GW of new baseload nuclear power.

Since then, I have taken an interest in the alleged South African Russian Nuclear Deal and collected information from various sources to try and make sense of what occurred.

The topic has come to attention again following the recent exchange between Dr. Kelvin Kemm, the former Chair of the Nuclear Energy Corporation of South Africa, and Kevin Mileham, the Shadow Minister of Energy for the Democratic Alliance.

In my view the fear of the excessive cost of nuclear power, and of corruption, under the right contractual conditions is completely irrational if one evaluates the facts objectively. Dr. Kemm is correct when he says that there is no reason to believe that nuclear power lends itself to more corruption than any of the other major energy sources (wind, solar, hydro, coal, oil, and methane).

Dr. Kemm is also correct that there is simply no evidence of a signed nuclear agreement with Russia.

The evidence seems to be overwhelming that:

(a) there never was, nor could possibly have been, a “nuclear deal”,

(b) the R1 trillion amount was a fabrication,

(c) the court never ruled against either a “deal” or nuclear power, and

(d) a nuclear power plant could be completed within five or six years from the point of first concrete and eight to ten years from the time of approval.

The “Russian” Nuclear Deal

The alleged deal that took place between Russia and South Africa was brought to the attention of the South African public by the journalist Karyn Maughan in her book titled “Nuclear: Inside South Africa's Secret Deal”.

The Russian nuclear deal was said to begin in 2014 when then President Jacob Zuma received treatment in Russia after being poisoned. According to her, Zuma had a belief that the CIA was out to get him and therefore he had to go to Russia for treatment. It is during this time that he allegedly agreed informally with Russian President Vladimir Putin to construct 9,6 GW of nuclear power plants. Putin was “anti-western” and therefore that made Russia in the eyes of Zuma the ideal vendor.

There are also other allegations in her book such as the now classified Project Spider-Web Dossier and the attempt to undermine the Treasury. These allegations came up in the Zondo Commission during the testimony of the finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, but the Zondo commission didn’t find any evidence of a Russian nuclear deal. I have no special insights on these political matters or their relevance on the nuclear deal, but note that the case against Matšhela Koko – the alleged State Capture Kingpin – was thrown out by the Middleburg Magistrate Court, because of the unreasonable delays. This is understandable given that the arrests were made over a year before the court struck the case from the roll and that the National Prosecuting Authority couldn’t bring anything substantial against him.

These matters aside, I quote below from official documentation to show why the major claims that there was a signed deal are highly implausible.

The joint cooperation-agreement

Miss Maughan, in her book, suggest that the Russian-South African deal came to fruition on September 22, 2014 during a joint announcement between the then South African Minister of Energy, Tina Joemat-Pettersson, and Rosatom. With the minister saying the following at the event.

“According to Ms Tina Joemat-Pettersson, ‘South Africa today, as never before, is interested in the massive development of nuclear power, which is an important driver for the national economy growth. I am sure that cooperation with Russia will allow us to implement our ambitious plans for the creation by 2030 of 9,6 GW of new nuclear capacities based on modern and safe technologies. This agreement opens up the door for South Africa to access Russian technologies, funding, infrastructure, and provides a proper and solid platform for future extensive collaboration’.”

The joint cooperative agreement with Russia does mention the 9,6 GW of nuclear capabilities, but is not a contract for it.

“The Parties shall create the conditions for the development of strategic cooperation and partnership in the following areas:

(i) development of a comprehensive nuclear new build program for peaceful uses in the Republic of South Africa, including enhancement of key elements of nuclear energy infrastructure in accordance with IAEA recommendations

(ii) design, construction, operation and decommissioning of NPP units based on the VVER reactor technology in the Republic of South Africa, with total installed capacity of about 9,6 GW.”

But what is not mentioned is that Minister Joemat-Pieterson also signed a similar agreement with France and China at that time. The website Politicsweb, for example, reported wrote the following on the 14 October 2014 on the deal with France:

“South Africa is pleased to continue the long-standing cooperation with France, as this paves the way for establishing a nuclear procurement process. To date, South Africa has concluded several Inter-Governmental Agreements and will proceed to sign similar agreements with the remaining nuclear vendor countries in preparation for the rollout of 9.6GW Nuclear New Build programme, remarked Minister Joemat-Pettersson.”

The text from the French-South African joint cooperative agreement reads the following.

“(b) use of nuclear energy for electricity generation, including the design, construction, operation and decommissioning of nuclear power plants in the Republic of South Africa, with total installed capacity of about 9.6 GW, and the fabrication of nuclear fuel.”

South Africa also signed a similar agreement with China as the website World Nuclear News reported on 10 November 2014:

“According to a statement from the South African energy ministry, the agreement ‘initiates the preparatory phase for a possible utilization of Chinese nuclear technology in South Africa.’ It added, ‘The government has reaffirmed its commitment to expand nuclear power generation by an additional 9.6 GW, in line with the Integrated Resource Plan 2010-2030, as a means of ensuring energy security and contributing to economic growth’.”

The Chinese agreement reads the following:

“The Republic of South Africa is planning civil nuclear energy new-builds with a total capacity of 9.6 GWe, with the aim of satisfying the increasing power demand, reduce carbon emissions, facilitate localisation for industrialisation, economic and social development, and is also willing to conduct cooperation with the People's Republic of China based on the significant on-going and long-standing cooperation between the two countries.”

I have two written statements from Rosatom South Africa on their perspective. Rosatom asserts that Miss Maughan did not take their response into account when she wrote her book or reported on the topic. Their exchanges can be found in the following link, and I quote.

“Never in the history of Russia-South Africa relationship were any type of binding documents on nuclear new build programme signed. There were no deals, no contracts, no nothing. Instead, several cooperation papers were signed: an Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) and two Memorandums of Understandings (MOU’s).

The IGA on “Strategic Partnership and Cooperation in the Fields of Nuclear Power and Industry” was signed in September 2014. It was intended for laying the foundation for a strategic partnership, which would focus on the development of a comprehensive nuclear new-build programme. Again, the IGA is not a contract, nor does it guarantee a contract. The IGA merely refers to what Russia was willing to provide if chosen as the preferred vendor at that time. South Africa signed similar intergovernmental agreements with China and France, which expressed interest in assisting South Africa with its nuclear ambitions”.

Additionally, during my presentation on the future of nuclear power to the South African Free Market Foundation in September 2023, Dr Thapelo Motshudi, the Chairperson of the Nuclear Energy Regulator of South Africa from 2016 to 2023, was in the audience. He told me that he also inquired about the alleged “Russian Nuclear Deal” and requested more details from the Daily Maverick, Mail and Guardian, Radio 702, and other outlets that ran with the story. They have been unable to provide him with evidence of a signed agreement.

What should one conclude from the above, Rosatom’s statements and the opinion of the Regulator? That Miss Maughan did not distinguish between or understand the difference between a cooperation agreement (which usually precedes a nuclear or other procurement agreement) and how Engineering Procurement and Contracting (EPC) works in practice.

Request for Information?

Eskom's Request for Information (RFI) from 2016 does not specify a Russian vendor. An RFI typically marks the initial stage of a tender process, where the buyer seeks basic information about available plants that would be chosen for construction, their costs, and the contracting structure. The RFI in question omits specific cost details, as it is the responsibility of the vendor to propose associated expenses.

Given this context, the question arises: How did we arrive at accepting the R1 trillion figure before the vendors could respond? Who performed these calculations and on what proposal or cost structure did they base their analysis?

France’s Position

During that period, one of my lecturers at ESTP Paris, employed by AREVA (that is now part of Electricité de France), shared insights from his recent visit to South Africa and inquired whether I worked for Eskom (for the record I have never had any relationship with them or been employed in the nuclear industry in South Africa).

He revealed that the French State had mobilized a team to participate in the anticipated 9,600 MW mass build tender. The French nuclear industry was set to invest approximately €20 million in responding to the tender. They were confident in South Africa's commitment to a nuclear build program and that the process would be competitive. Despite challenges and overruns in recent projects like Flamanville, Hinkley Point C, Olkiluoto 3, and Taishan, the French state still viewed the mass build program as a worthwhile venture, and they were willing to absorb the overrun costs.

They remained optimistic that offering a competitive price would prove advantageous, and the nature of the larger build would result in an economy of scale. This confidence was rooted in the enduring 40-year relationship between France and South Africa in the Nuclear Sector dating back to the construction of the Koeberg nuclear power plant, and AREVA winning the 2014 life extension contract.

France proposed financing the mass build program through the Exeltium Model. This proposal envisioned allowing various stakeholders, such as those in the automotive industry in Port Elizabeth, to invest in the nuclear power construction. The French state would then finance the build through low-interest loans, a crucial aspect as it effectively accommodates potential cost overruns.

The general concept is shown below.

Again, why would France go this far if they knew that South Africa already signed a deal with Russia?

My understanding is that the Americans, South Koreans and Chinese also went as far in their effort, because they were opening offices in South Africa, in anticipation of having a fair chance of winning.

Koeberg’s Life extension

Mr Mileham furthermore expressed skepticism about the cost of Koeberg’s life extension which was estimated at R20billion in 2010. While I support his call for transparency, I do not find the numbers unusual.

In 2014, AREVA won the life extension contract for the Koeberg Power Station, further solidifying their confidence as a top contender for the 9,600 MW reactor by proposing a 6-unit European Pressure Water Reactor (6 x 1600 MW = 9600 MW).

Doing a basic calculation, based on the Dollar-Rand exchange rate in 2010 (R7.31 to the US$), $20 billion would be $1367/kWe for Koeberg. When adjusted for inflation and currency fluctuation, it would be $555/kWe, in line with the OECD values shown in the table below from the OECDs “Projected Cost of Electricity Provision” report.

Since nuclear contracts are often negotiated over the long term, they appear high, because they must anticipate price inflation.

Cost of new build

The general skepticism against new nuclear builds is based on assumptions that cost overruns could be excessive. This reflects a misunderstanding of country-to-country transactions as the construction risk is typically shouldered by the vendor, not the buyer. This misconception was evident in the Stellenbosch University Prof. Mark Swilling's reference to the finance agency Lazard. He was quoted in an article in the website mybroadband that appeared on the 15th of December 2023. I have sent him an email on the error, but he hasn’t responded yet. Lazard's cost figures appear biased toward France and North America, displaying a notably unrealistic capital expenditure that overlooks lower prices in Asian markets.

The following graph shows the 2019 cost range for ongoing nuclear new builds. These numbers are from the "Cost Drivers of Nuclear Power" report prepared by a UK Government Task force for the UK Industrial Strategy and Clean Growth Strategy. Subsequent studies at MIT found similar numbers as has the OECD’s Nuclear Energy Agency.

The sensible cost estimates for new builds for country-to-country transactions range from $5000/kWe initially, gradually decreasing to $4000/kWe, and even as low a $3000/kWe, for the final units, factoring in potential overruns. It is noteworthy that the midpoint value of $4500/kWe is precisely the same figure on which Kevin Mileham and Dr Kelvin Kemm concurred. Using the 2016 dollar to rand exchange rate of R14/$1, it would have resulted in a R500 billion deal at the time, that is half the cost of the alleged R1 trillion. Other analyses, such as those of Dr Anthonie Cilliers, then Professor at Potchefstroom University, and Dave Nicholls, Chair of the Nuclear Energy Corporation of South Africa, suggested a R650 billion cost. Regular critiques of nuclear power such as Chris Yelland concluded as high as R776 billion.

It’s worth noting that this money would have been spent over a long period of time and a mega projects of this nature usually have a knock on effect in the economy, making it entirely affordable for South Africa.

Cost overruns

The interest rate at which a nuclear deal would have been financed would have been impossible for Miss Maughan to know, simply because there is no evidence that South Africa signed such a deal with Russia.

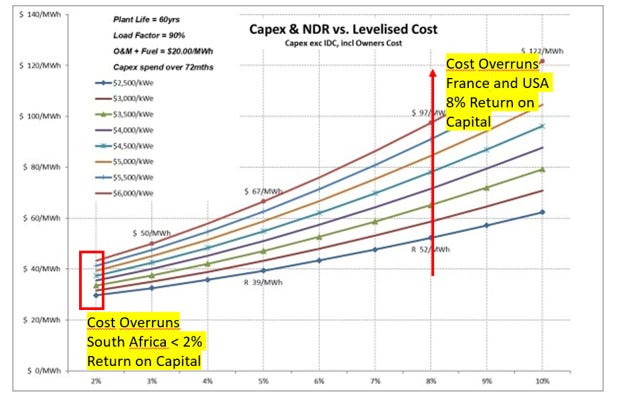

The high costs that are cited often come from the Financing Agency Lazard, which Prof. Mark Swilling, for example, cited. But he neglected to note that country-to-country transactions entail vendors absorbing the cost overruns. This is normally done through a low interest loan of less than, say, 3%. As the graph below shows, even with overruns, a nuclear new build in SA could not possibly entail the high costs that critics claim. The levelized cost of electricity depends on the discount rate.

Construction Time

The average construction times of nuclear new builds in western countries have been rather poor during the last few years, yet in the eastern countries they do seem to be on track. As the graph below shows, from the day of first concrete, it normally takes around 60 months or 5 years to complete the construction of a nuclear power plant (NPP), and not the 10 or more years alleged by critics.

A large new reactor might take 10 years from the decision to proceed. The process includes many aspects, such as feasibility studies, impact, and safety assessments, site selection and the like. South Africa already has two sites selected for a NPP, Duynefontein next to Koeberg and Thuyspunt in the Eastern Cape, and has an established and sophisticated nuclear regulatory framework . Therefore the 10-year estimate put forth by Kevin Mileham is at the upper limit. Had South Africa advanced the NPP in 2016, then it is likely that the first reactor units could already be, or would soon be, completed.

The Barakah Nuclear Power Plant took around 8 years to complete. The time allocated include a 2-year delay due to covid and 150 South Africans were part of the project. Why would South Africans build slower in their own country than abroad? In fact, we are in communication with numerous such engineers, who are looking forward to working on South African Nuclear builds. They had no choice but to seek employment elsewhere when the nuclear extension program in South Africa was canned.

The final cost calculation of the Barakah Reactors showed a traditional learning curve of a 10% reduction per unit as a report from the Norwegian consultancy Rystad Energy. The average number for the 4 units came at $4275/kWe, in line with the estimates put forth by both Mr. Mileham and Dr. Kelvin Kemm. They therefore confirm, once again, that there was no evidence of a R1 trillion deal.

Anti-Nuclear Activism and the court case

How anti-nuclear activism affects public participation and energy policy in particular, is a matter of ongoing academic research. In July 2023 Christian Harbulot at France’s Ecole de Guerre Militaire, for example, observed that German think tanks are undermining France’s nuclear security and the uranium supply chain abroad. Ken Braun from the Capital Research foundation has shown that anti-nuclear lobbyists receive around $2.1 billion annually in the United States of America.

When I spoke to Ken Braun about the money involved, he told me that the two activists concerned with South Africa’s nuclear deal, Makoma Lekalakala and Liz McDaid received the Goldman Prize in San Francisco. The event was funded by The World Resources Institute (WRI). The WRI reported a handsome total revenue of $289 669 226 for the year ending September 2021. Some of these donors include the European Climate Foundation, the Shell Foundation, Facebook, the Toyota Mobility Foundation, the Walmart Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

In an interview with Earthlife Africa’s Director, Makoma Lekalakala, published in the Harvard Law Review in 2018 on the question of whether the South African Government would continue to make ‘secret deals’ for energy provision, Lekalakala made the following statement in her response, confirming that the issue was not about nuclear energy technology, but rather about the procurement processes involved in energy generation:

“What we've seen is that, with the nuclear issue, we challenged the procurement of nuclear energy. That's what the case was all about. It was not about technology. And the bureaucrats came back, ignoring the court ruling, wanting to resuscitate the process again, and we had to take them to court again. Then, they came back again last year, and we had to remind them of the admission that was made by the previous minister that they would not go ahead, and they’re still trying to [go ahead].”

The court case that was brought by Earthlife Africa furthermore does not mention the nuclear deal, instead the judge ruled on procedural irregularities. In addition, the alleged R1 trillion calculation that was based on the cost of the Egyptian Nuclear Deal was not opposed, and neither was the substantial discount afforded through economies of scale taken into account.

In 2017, Earthlife Africa obtained a court judgment against the Minster of Energy regarding nuclear power procurement. The judgment was widely misconstrued and misrepresented, perhaps maliciously, as a judgment against nuclear power per se. It was no such thing. The court did no more than rule against a procedural technicality. It found merely that the government had not met procedural pre-conditions for a “determination” regarding possible nuclear power procurement. It was merely a judgement on procedural technicalities, which could have applied equally to, say, renewable energy or fossil fuel power. Or, for that matter, any other procurement such as for housing or healthcare.

Earthlife Africa still refers to a supposed “Corrupt Nuclear Deal” which it supposedly “stopped”. The court found neither corruption, nor even a “deal” to stop. There was and could not have been such a deal. That was always obvious.

All that was in issue was whether the Minister complied with procedural technicalities, before tabling her “determination” regarding prospective nuclear power to Parliament. At no stage before, during or after the judgment was anything preventing the Minister from proceeding as required. I have not found reasons for the government not proceeding with the matter.

Prior to a determination that new generating capacity might be required, the government must follow a simple ‘procedurally fair public participation processes’ in terms of the 2006 Electricity Regulation Act (ERA).

There was never a prospect of a finding against the alleged ‘nuclear deal’. The so-called deal was not even mentioned.

The way forward?

Now that the South African Government has decided again to proceed towards a nuclear power “determination”, all that is required of it is to comply with the judgement. In fact, the judgement changes nothing. It amounts to no more than a declaration of what was obvious.

I suspect that the dubious R1 trillion number might have been derived from the cost of an Egyptian nuclear deal without allowing for economies of scale.

The R1 trillion notion is repeated in the World Nuclear Status Report, a document funded by such anti-nuclear lobbyists as Amory Lovins and Mycle Schneider. Lovins’s organization The Rocky Mountain Institute received generous donations from the oil and gas industries and Schneider’s publication has previously received money from the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection. The section on nuclear power in South Africa is written by Prof. Hartmut Winkler at the University of Johannesburg who is a notable public critique on nuclear power in South Africa. In fairness to him, Prof. Winkler has openly discussed his differences with me. He does not claim to be “anti-nuclear” in principle, but rather that his primary concern is the cost and lead time.

However, it is also worth noting that Lovins co-authored articles with Dr Anton Eberhard at the University of Cape Town who, in 2017, suggested that “the gloves must come off against nuclear power”. When I asked Eberhard in an email to clarify our differences on nuclear power, he said that he was “too busy” and referred me to a few sources that include, among other Schneider. Eberhard is associated with energy producers with powerful vested interests against nuclear power competition and therefore, in my view, he should refrain from making public statements on the subject.

Conclusion

So, what can one conclude from the above?

The evidence seems to be overwhelming that:

(a) there never was, nor could possibly have been, a “nuclear deal”,

(b) the R1 trillion amount was a fabrication,

(c) the court never ruled against either a “deal” or nuclear power, and

(d) a nuclear power plant could be completed within five or six years from the point of first concrete, and eight to ten years from the time of approval.

Earthlife Africa’s recent representation on the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) should raise even more questions from the wider public. The PCC for example uses flawed data such as the Finance Agency Lazard, and given that it is staffed with open anti-nuclear activists, South Africans should question the claims regarding nuclear power that come from this conflicted body. They are influencing our future electricity mix. Sadly they seem to be surrounding our president and ministers of energy, minister of environment, and electricity at a time when the country is experiencing rolling blackouts.

The South African public was misled regarding nuclear power. If the truth finally becomes apparent, the widespread misinformation that there was a 'Russian Nuclear Deal', should be deemed a significant factor behind the current issue of load shedding.

During the same period that we fought over it, our engineers successfully constructed a nuclear reactor in the UAE within an impressive timeframe and budget. Whether we permit a similar achievement to occur again depends on us, particularly if the influence of environmental enthusiasts continues to shape our policy decisions.

Historians may condemn those who perpetuated the story of a “Russian Nuclear Deal” without evidence, absolve those at Eskom, the South African government and in Russia, from a crime that they never committed. They will affirm the words of Sir. Francis Bacon that truth is ultimately the daughter of time and not of authority.

About the Authors:

Olivia Vaughan is the Director of Westman Vaughan Pty Ltd, a strategy company specialising in Trans-boundary Circular Economy innovation in which capacity she heads stakeholder relations at Stratek Global Pty Ltd. She is an investor in businesses spanning multiple industries and holds a Bcom Law and MBA from the Northwest University. She is based in South Africa.

Hügo Krüger is a YouTube podcaster, writer and civil nuclear engineer who has worked on the design of various energy-related infrastructure projects, ranging from Nuclear Fission, Nuclear Fusion, Liquified Natural Gas and Offshore wind Technologies. He currently resides in Paris and regularly comments on energy and geopolitical matters.

Leon Louw, Free Market Foundation Founder and retired President. Internationally recognised Nobel Peace Prize nominee, author, and policy analyst. He is the CEO of the Izwe Lami Freedom Foundation.